The comeback of the mechanical watch has been nothing short of a miracle, except when it hasn’t!

On the one hand, we’re talking of a marvel of Lazarus proportions, because who would have thought during those dark days of the Japanese quartz invasion that Swiss analogue watch making would awaken from its death throes to live, thrive and, once again, bite the hand that fed it. In the late 1970s, as Neuchâtel fell, Geneva surrendered, and Biel-Bienne, and Grenchen were waving white flags, the joke was that the only chance of survival the Swiss had was to make their mechanical watches out of cheese and offer free yodelling lessons as part of a value-adding package!

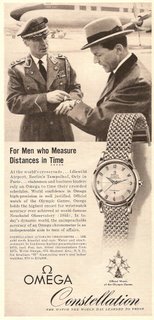

Why, when the clamour for all things digital is reaching new and ridiculous heights, is the analogue/mechanical watch enjoying such a return to favour? The answer is that more than a measure of the magician’s art has shadowed the revival of the analogue watch. Over the last two decades, some very clever and inimitably Swiss sleight-of-mouth has convinced an army of cashed-up individuals to part with their money and sign up for analogue watches.

Some of the zeal for new analogue timepieces is fuelled by those who have joined the ranks of what I term the ‘horological petrol-heads’. These are the Knights Templar of the horological world, mainly men, who are driven by the intrinsic beauty and engineering of high end timepieces and who also have a love and deep respect for the unique culture and heritage of 400 years of fine watch making. You’ll find them sharing their knowledge and passion in watch forums, in fact, anywhere that other horological petrol-heads congregate.

The other, much larger group, consists of ‘Brand Junkies’ and ‘Wannabees’. Brand junkies are usually, but not always, moneyed professionals who have a wardrobe stuffed with Italian suits, a garage that houses one or two very good marques, a boat, ideally a history of indiscretions and money to burn on brands. They are, above all else, compulsively acquisitive. There’s nothing wrong with using one’s wealth to buy the finer comforts in life, but brand junkies and wannabees have fallen for some very creative marketing hype about the exclusivity of many brands of Swiss mechanical watches that don’t stand up to exclusivity tests.

The brand junkie’s compulsion to collect high-end ‘names’ or the products of Haute Luxe celebrities has more to do with vanity inflation, the need to feed a status habit, or the deep hope that some of the brand’s exclusivity will rub off on him, or her. Wannabees are driven by similar urges, but don’t have the readies to become fully paid-up members of the Brand Junkie brigade.

Because of their primary interest in ersatz exclusivity and their disinterest in the engine that powers the brand, brand junkies have been the target and indeed the greatest victims of the Swiss industry’s sleight-of-mouth activities. Ask your average brand junkie what a ‘manufacture’ is and s/he is more likely to say that it has something to do with telling strategic lies, than explaining that a manufacture is a top-end watch making ‘house’ that makes all of the components and parts of the watch movement in-house. A number of Establisseurs (factories that only engage in assembling watches from parts manufactured by specialist suppliers)are keen to help them maintain their ignorance.

Some brands are produced by marques that form part of the Swatch conglomerate, amongst which are famous names like Breguet, Blancpain, and, of course, Omega. The Swatch Group manufactures nearly all the parts required to produce complete mechanical watches, and if you consider it as one 'house' then it follows that the aforementioned brands are from a manufacture.

The right course appears to be to consider each model on its merits: where Swatch produce movements that are exclusive to one of its brands, then it's fair and reasonable to award high points for authenticity and exclusivity. Where a Swatch brand shares a movement with other Etablisseurs then one should allow lower marks for authenticity and exclusivity.

Brand junkies will pay thousands of dollars for brands powered by 'ebauches (Third-party movements, parts and components manufactured by suppliers of movements). A lot of watch ‘brands’ buy their movements and conceal that fact by engraving their names on the plates and rotors. The ETA 2892 movement is one of the more common ‘ebauches that sits under many of the swankier and expensive names to which brand junkies gravitate.

What’s this got to do with collecting Omega Constellations of the 1950s – 1970s? Read on, and all will be revealed.

Rolex had, on occasions, and Panerai use ebauches, notwithstanding the fact that they chose/choose one of the finer engines on this planet, namely the famous Zenith El Primero movement. Some other European brands buy Japanese movements and some are buying Chinese movements.

The use of ‘ebauches is not the problem. The cottage industry tradition in Swiss watch making institutionalised the use of ‘ebauches. They were originally made by rural folk as a winter pastime when they and their cows had to stay indoors because of the severity of the Swiss weather.

It is the failure of many of the upper market brands to tell their customers that their watches are powered by ‘ebauches that is the problem. What makes it even more galling is that the propaganda of many of these brands milks the exclusivity line for all it’s worth.

Some of the better houses do use high end ebauches from manufactures like Jaeger LeCoultre and modify them, work up a good finish, add more jewels, etc., and the finished product is significantly different from the base calibre, thus elevating the exclusivity factor.

But, many of the swankier fashion marques that attract brand junkies as effectively as jam does flies are powered by relatively cheap or ubiquitous 'ebauches and not all that well finished. If history is anything to go by, these brands will depreciate rapidly over a decade or so to the point where they have not much more value than the novelty of the case design and the worth of the metal from which they’re made.

So if you are looking for both horological and monetary value, which houses actually make their own movements? Brands like Jaeger-LeCoultre and A. Lange & Söhne are true ‘manufactures’ because they use their own in-house movements, while brands like Patek Phillipe, Audemars Piguet, Zenith, Chopard and Piaget will sometimes use ‘ebauches for particular models and in-house movements for others. These brands offer true value, exclusivity and much higher levels of future collectibility, but they are very expensive.

There is a rush by some brands to mend their ways and manufacture some of their movements in-house, perhaps because they believe that, sooner rather than later, the game will be up, and brand junkies will begin to make distinctions hitherto unheard of. Let's hope the fashionistas don't throw the baby out with the bath water and declare all 'ebauches out of bounds, or out of fashion.

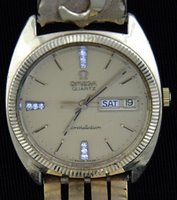

This leads us to Omega Constellations of the 1950s to the 1970s. The 300, 500, 700 and 1000 series of chronometer movements were all made in-house by the Omega Watch Company before it was swallowed by the conglomerate that eventually became the Swatch Group. They were some of the best movements ever made and this gives them intrinsic and horological value, ensuring their future collectibility.

The most important point of difference when buying any watch is the movement. Whether buying new or vintage, give equal consideration to case design, metal content, whether the brand has an in-house movement, and, if not, the degree to which the base calibre has been modified and finished. This will give the watch true credibility, authenticity and real, not imagined, exclusivity.

(c) Desmond Guilfoyle, 2006