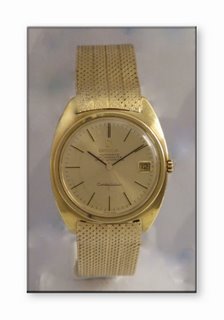

Omega Men’s Constellations of the 1950s to the mid-1970s are one of the most collectible branches of the Omega family. ‘Connies’, as Omega enthusiasts call them affectionately, are beloved offspring of the golden era of watchmaking, an era that reached its high point in the late 1960s. Embodying a combination of style, precision and quality, Omega Constellations, particularly ‘Pie Pans’, have attracted renewed interest as the mechanical watch continues its strong comeback.

It wasn't all that long ago that the mechanical wristwatch looked as though it was going to go the way of the typewriter. In the late 1960s, Swiss and Japanese watch houses invented movements that used the vibrations of a quartz crystal to keep time. Within a few years, cheap mass-produced quartz watches flooded the market and the venerable Swiss watchmaking industry was brought to its knees.

Strange as it may seem, talk of the demise of the mechanical watch created the impetus for its survival. The prospect of the mechanical watch era coming to an end stirred an interest in collecting them. By the middle of the 1980s, the vintage watch market was buoyant, and, apart from a few slumps caused by prevailing economic conditions, the demand for vintage watches has continued to grow.

There are two forces driving the mechanical watch comeback. Wealthy males, businessmen and other acquisitive types looking for status symbols beyond those of boats, cars and Italian suits, are active in the high and middle ends end of the market, buying both new and vintage mechanical watches. The other group is made up largely of men who love engines – horological ‘petrol-heads’ – and they are active in all segments of the market. These collectors are more interested in the movements of watches, the aesthetics of case design such as flawless finish and smooth amalgamation of lines, and the boyish thrill of watching beautifully finished wheels, gears and cogs purring and oscillating. As collector Mathew Watson puts it,

“It is like an living organism with a heart that beats like ours and where wheels spin around each other and work together to form a machine that enables us to keep time. And then you see the beauty of the tiny, machined parts, the wheels set in ruby and gold and the craftmanship that created it all”.

What lad could resist that?

Omega Constellation timepieces, notably Pie Pans, attract devotees from both groups of collectors. It is the engineering, beauty, functionality and great pedigree of these watches that makes them so alluring to investors, the status conscious and horological petrol-heads alike. Another attraction of Constellations is that they were manufactured at a time when mechanical watchmaking technology had reached a high point, and so they can be worn and not coddled. The introduction of white alloy hairsprings dramatically improved their timekeeping capacity and the invention of jewelled shock absorbing systems meant they could withstand the bumps and grinds of daily life.

In the 1950s and '60s, Omega enjoyed a status equivalent to Rolex, achieved through the production of innovative, high quality and relatively affordable timepieces. The Constellation was one of the finest and most accurate watches available at the time and catered to different budgets and tastes with a choice of stainless steel to solid gold cases and simple to lavishly styled dials.

From the outset, Omega concentrated on making the external appearance of the Constellation distinctive. The first dial was strikingly luxurious, featuring gold hour markers with sloping planes complimented by a convex twelve-sided dial, reminiscent of a pie pan.

The early 1950s automatic Constellations usually featured a calibre 354 hammer self-winding design (Known colloquially as a Bumper Movement). These movements were not new to market and had more than a decade of development before they were earmarked for the Constellation range. A dream of any Constellation collector is to own the Grand Luxe Constellation which has hooded lugs and, occasionally, a solid gold ‘brickwork link’ bracelet. Constellations watches were powered initially by a the calibre 352 Rg movement, which was the deluxe execution of the chronometer-graded movement.

The Bumper movement was replaced in 1956 with a calibre 501 movement that featured a central rotor self-winder. It was superseded quickly by a calibre 505 movement, and in 1959 was replaced by the famous Calibres 551 and 561 (with date). In 1966, Calibre 564 with quick date change replaced Calibre 561.

The Omega Constellation 551 Certified Chronometer was one of the finest watches of the 1960's and this makes it particularly collectible. It had a power reserve of 50 hours and was similar to Calibre 550. It was a 24 jewel watch with a four arm ‘gluycdur’ (beryllium) balance, allowing the spring to maintain its strength, shape and anti-magnetic quality. Fine timekeeping was achieved through the micro-regulator.

The 500 series was designed by Marc Colombe under the direction Henri Gerber. The series has proven over time to be the most precise and indeed the most celebrated movement series in the history of the Omega company. The success of the series 500 owes much to its tremendous reliability and a number of ingenious improvements, amongst which are the self-winding mechanism and the mobile balance spring stud holder: the latter an improvement invented by Jacques Ziegler.

The main differences between this Omega and the famous Rolex Calibre 1570 are in the balance wheel and hairspring. The Rolex has a white alloy hairspring with a Breguet overcoil, whereas Omega used a flat hairspring made from Beryllium that allowed for adjustments by a micrometer screw "swan-neck" regulator.

Omega in the 1960s was in the vanguard of technological development in the watch industry and made vast improvements to the standard of quality as it applied to large-scale watch manufacturing. The 500 series benefited from this eruption of ingenuity, which included high tech manufacturing technology such as a 1962 Pierre-Luc Gagnebin invention called the Omegatronic, a revolutionary system for measuring the torque of balance-springs.

By 1969 Omega was producing more than 194,500 Constellations a year. The Constellation was chiefly responsible for expanding the commercial reputation of the company and allowing it to further its aims in the prestige market sector.

Constellation Calibres:

If you are about to begin collecting these beautiful timepieces you would be well advised to learn as much as possible about the calibres of movement used for Omega officially certified Constellation chronometers.

Because of the popularity of Omega Constellations, particularly the Pie Pans, numerous ‘Frankenwatches’ have appeared. The widespread use of Pie Pan dials with non-certified movements, often from the Seamaster and Geneve lines, or watches that have been made up of parts from other Omega non-certified movements, demands strong buyer awareness.

Fortunately, the calibres of Constellations from the first Bumper movement to the nineteen seventies are few, and this is good news to collectors of the pie pan dial Constellations particularly. If you stick to the following descriptions of the 300, 500, 700 and 1000 series calibres, you can be reasonably assured that you won’t be acquiring a ‘monster’ created by some fiend or swindler in his workshop.

Calibres for the bumper movements were 352 Rg, 354 Calibres 352 and 354 were based on a design by Charles Perregaux under the direction of Henri Gerber and known in-house as the 28.10 mm which was a slightly smaller movement than the famous 30.10mm, but essentially both movements shared the same fundamentals. The bumper used an oscillating weight that wound in one direction. Over 1.3 million of these movements were produced between 1943 and 1955. They are a classic: well designed, made robust to handle the strong vibrations caused by the hammer action and still going strong on the wrists of owners of early automatics, Seamasters and Constellations. Over half a million of these movements were certified chronometers.

The 500 series self-winding movements, 501, 504 with date and 505, replaced the bumper movements. In 1959, new Constellations were powered by certified Calibres 551 and 561 with date. In 1966 Calibre 564 was introduced with the quick date feature.

The success of the series 500 owes much to its tremendous reliability and a number of ingenious improvements, amongst which are the self-winding mechanism and the mobile balance spring stud holder: the latter an improvement invented by Jacques Ziegler.

The rarer Calibre 700 series Superflat movements came in both solid white and yellow gold, some had a solid gold balance of which only 12,500 pieces were made. Calibre 711 came in solid gold and stainless steel cases, while the superflat 712 without second hand was available in solid yellow and white gold and stainless steel.

The movements powering Omega Constellations up until the end of run for the 500 series (including the 750s) were all produced in-house as were the 1000 series designed in 1968 by Kurt Vogt under the direction of Alfred Rihs.

The 1000 series was one of the best-selling of all Omega self-winding calibres. More than 1.5 million were used not only as certified chronometers in Constellations, but also as uncertified movements in Seamasters, Geneve’s and Speedmasters before Omega outsourced its manufacture of mechanical watch movements in the later 1970s.

The early 1000 series movements are not held in as much esteem by collectors. The newly designed winding mechanism and the self-lubrication system created problems with reliability. Calibres 1000, 1001 and 1002 are best avoided, except by those who can repair and maintain them. However, Omega soon fixed the problem by eliminating the self-lubrication system and instantaneous date setting device as well as making improvements to the winding mechanism.

Calibres 1011 (1972-74) with cases in solid gold, gold bezel and stainless steel, 1012 (1977) gold plated version, 1020 (1978) in both solid gold and gold bezel, 1021 (1972) in both solid gold and stainless steel are well worth collecting. These calibres were some of the very last in-house movements made by Omega, and because of their higher frequency (28,800 a/h) they allowed better regulating performance, certainly holding their own against the onslaught of Quartz movements that occurred in the 1970s.

(C) Desmond Guilfoyle 2006